Gone in the Night: The West Virginia Co-Ed Murders

The Last Ride

In the winter of 1970, Karen Ferrell and Mared Malarik, both nineteen, were freshman at West Virginia University in Morgantown. Young and fearless, the roommates would often hitchhike from their dorm in Evansdale to the main campus less than two miles away. While it wasn’t unusual to encounter a shady character every now and then, they had always managed to arrive at their destination safely.

On the afternoon of Sunday, January 18th, the girls had ventured into the city to see a showing of the musical Oliver. By the time the movie was over, night had fallen. Rather than braving the sub-zero temperatures, they decided to hitch a ride back to their dorm. Witnesses would later report observing the pair getting into a light-colored sedan driven by a man who appeared to be in his early forties. It was the last time they were seen alive by anyone other than their killer.

The next day, when it was discovered that Mared and Karen hadn’t made it back to Evansdale, a missing person report was filed with the local police. Believing that the pair had left of their own volition, authorities waited several days before launching a search. With the trail having gone cold, no traces of the coeds were found. When the long winter finally gave way to spring, investigators got their first break.

In March, a thirteen-year-old boy found Mared Malarik’s purse lying in some weeds just off US-119. A few weeks later, another boy happened upon Karen Ferrell’s weather-beaten driver’s license in a remote area just south of Morgantown.

Encouraged by the discoveries, members of the state police scoured the outlying areas for additional clues. Their efforts paid off when a prescription pill bottle bearing Karen’s name was uncovered on the same dirt road where her license had been found. With more pieces of the puzzle turning up every day, investigators were confident that they were growing ever closer to finding the girls.

A Grim Discovery

Things took an unexpected turn on April 6th when an anonymous letter arrived at the state police barracks in Morgantown. Bearing a Maryland postmark, the correspondence included a crude map of where evidence pertaining to the missing coeds could be found.

With nothing to lose, officers followed the instructions, which led them to Goshen Road, a residential area of Morgantown. A search of the yards and surrounding woods turned up a pair of eyeglasses and a woman’s purse that had clearly been out in the elements for some time. Realizing that the letter might be their best hope of finding whoever was responsible for the girls’ disappearance, authorities utilized the services of the postmaster, as well as those of a handwriting specialist, to help track down the author.

A couple of days later, a second letter arrived that purportedly included a detailed description of where the bodies were located. Counting on lightning striking twice, police officers and volunteer searchers combed the area in question but came up empty-handed.

On April 14th, Governor Arch Moore called in the National Guard to aid in the ongoing quest to recover the remains of Karen Ferrell and Mared Malarik. Forty-eight hours later, two badly decomposed bodies were discovered after a member of the search party noticed a foot sticking out from under a pile of debris that turned out to be a carefully constructed tomb. The gruesome find was made all the more disturbing by the fact that the victims were missing their heads.

A third letter, which came less than a week after the bodies were unearthed, gave cryptic information regarding the whereabouts of the rest of the remains. Unfortunately, the writer’s convoluted directions had sent searchers chasing their own tails. As a result, the missing heads were never found.

Inexplicably, rather than being sent to a police agency, the fourth — and final— correspondence was mailed directly to Mared Malarik’s parents at their home in New Jersey. The rambling text mainly consisted of the writer’s baseless theory that the girls had been killed by a Satanic cult. An apparent expert on the subject, the author had implied that the severed heads had likely been used in black magic rituals.

Suspects Abound

After holding their cards close to their chests for several months, police announced in September that the source of the letters had been found. As it turned out, the communications had been sent by members of a pseudo-religious cult based in New Jersey called the Psychic Science Church. Believing that their leader had the power to channel spirits, they had used his gift to contact celestial beings who had given them insight into the case.

Following a thorough investigation into the group’s activities, they were cleared of any involvement in the murders. It was determined that the information they had provided — most of which proved useless — had not come from firsthand knowledge. And, with that, the investigation came to a standstill once again.

Things heated up with a vengeance six years later when, in January of 1976, the Morgantown police received a call from New Jersey authorities saying that they had someone in custody who had just confessed to murdering two coeds in West Virginia. Their hopes of finding the killer renewed, agents from the state police, accompanied by detectives who had been on the case since the beginning, set out for New Jersey.

Upon their arrival, investigators were introduced to thirty-six-year-old Eugene Paul Clawson, who had been incarcerated in Camden since 1974 for raping a thirteen-year-old-girl and a fifteen-year-old boy at gunpoint. With New Jersey officials on hand to witness the proceedings, the representatives from West Virginia prepared to interview the man they hoped would finally put the matter of what happened to Karen Ferrell and Mared Malarik to rest.

With a court reporter taking down every word, Clawson recounted seeing the girls hitchhiking on a busy downtown street on that chilly January night. His predatory instincts aroused, he had pulled up beside them in a cream-colored Chevrolet on loan from a friend and offered them a ride, which they had gratefully accepted.

Once he had them inside the car, he locked the doors and pulled out a gun. As the girls pleaded for their lives, he headed down County Road 76 towards the old Weirton Mine. After parking as far off the beaten track as possible, he had forced them to perform “unnatural acts” on each other before binding their hands and sexually assaulting them.

When he was finished, he ordered the girls to put their clothes on and get out of the car. After marching them into the woods, he had shot each one in the back of the head. In an effort to delay identification, he then beheaded the teenagers with a machete he had borrowed from his brother.

Knowing that he couldn’t leave the bodies laying out in the open, he dragged them further into the thickets and placed them on the frozen ground, side-by-side. Over the next hour or so, he had roamed the woods, collecting rocks, stone slabs, branches, twigs and anything else that could be used to conceal the evidence of his wrongdoing.

Once the above-ground grave was complete, he had taken the severed heads and driven to his brother’s house with the intention of showing off his trophies. After knocking on the door and receiving no answer, he had taken the remains and discarded them — along with the murder weapon — in a gully outside Marion, Pennsylvania, some two and a half hours from the scene of the crime.

Three days later, detectives searched the location Clawson described. Although they didn’t find what they were looking for, they did discover a pair of handcuffs and several wisps of hair. The latter was analyzed, but the technology available at the time wasn’t advanced enough to pinpoint the source of the strands, which had been cut from the scalp rather than being removed by force.

In May of 1976, four months after confessing to killing Karen and Mared, Clawson recanted. According to him, he had made the whole thing up after reading about the case in a true crime magazine. Since he hadn’t actually been involved in their deaths, he didn’t think that anyone would take him seriously. Unfortunately for him, since he had provided details that had not been released to the public, his seventy-five-page admission of guilt had spoken louder than his sudden pleas of innocence.

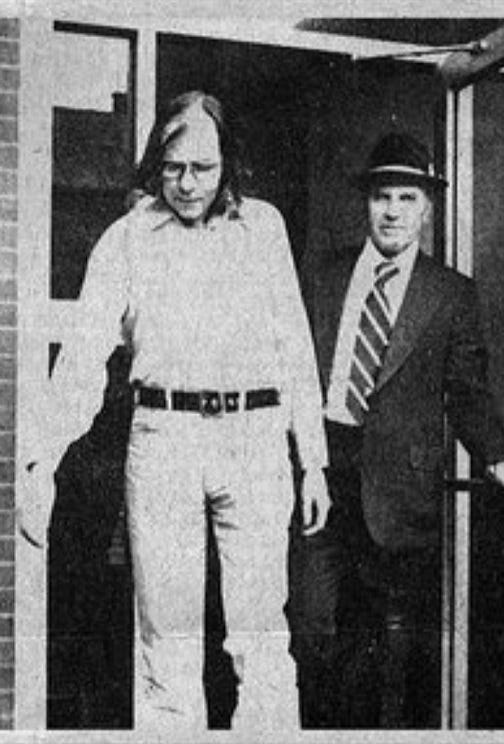

Later that summer, Clawson was indicted on charges of kidnapping, rape and first-degree murder in connection with the deaths of Karen Ferrell and Mared Malarik. In November, he was tried and convicted on all charges. Since West Virginia had abolished the death penalty ten years earlier, he received the maximum sentence allowed by law: life in prison without the possibility of parole.

When the appeals process got underway, his defense team had demanded that the verdict be thrown out on the grounds that Clawson had made the incriminating admissions without having an attorney present. They also argued that prosecutors had prejudiced the jury by showing them graphic images of the victims’ headless remains. As a result of their tireless work on their client’s behalf, a year into his sentence, the convictions were overturned.

Clawson was retried in 1981. Once again, he was found guilty by a jury of his peers and sentenced accordingly. Even though his second conviction all but ensured that the “Coed Killer,” as he had been dubbed by the press, would spend the rest of his life behind bars, his steadfast supporters refused to give up the fight.

Those who believed that Clawson was railroaded pointed to similar crimes that had taken place around the same time as proof that once authorities had his confession in hand, they had ignored other possible suspects.

One unsavory character they thought deserved looking into was the aptly named William Bernard Hacker, Sr. who had been arrested in Pendleton County, West Virginia in 1971 for decapitating a man and burying his remains in a wooded area. Even though the only resemblance between this murder and the slayings of Karen and Mared was the mutilation that occurred after the fact, those who rallied behind Clawson believed that this should have been enough to warrant reopening the investigation.

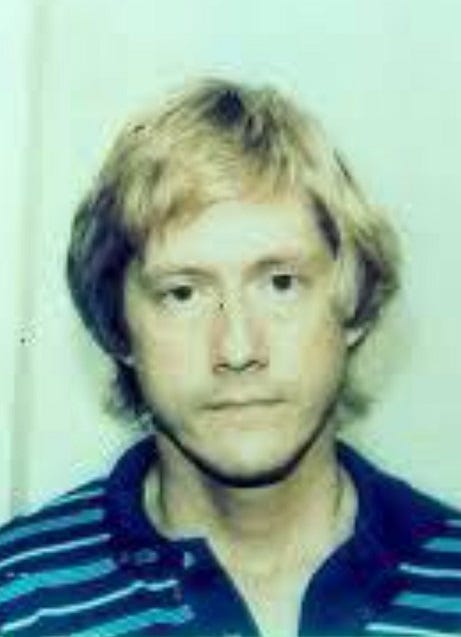

Another person of interest whose name cropped up was notorious “Vampire Rapist,” John Brennan Crutchley. An engineer who was seldom without female companionship, he never stayed in one place for very long. Coincidentally, whenever he moved to a new area, women started disappearing. This disturbing pattern was noted during the time he spent in Virginia, Florida and his home state of West Virginia.

Though Crutchley’s nomadic lifestyle had allowed him to fly under law enforcement’s radar for much of his adult life, famed FBI profiler Robert Ressler pegged him as having all the qualities of a serial killer. The crime that ultimately put him behind bars involved the sexual assault of a teenage girl he abducted in November of 1985 while his wife and child were out of town for the Thanksgiving holiday.

After escaping through a bathroom window, the victim had flagged down a truck driver, who had taken her to the hospital. When she was examined, it was discovered that nearly half of her blood supply had been depleted. According to her, every time she was raped, her attacker would put syringes in her arms and draw blood, which he would then consume in front of her. The emergency room doctor on duty the day she was brought in told police that she was only steps away from death’s door when she was found.

Although Crutchley was a sick individual, to be sure, linking him to the coed murders takes some doing. The fact that he was attending college in Washington, D. C. in 1970 when the crime occurred, coupled with his penchant for hunting close to home, effectively rules him out as the killer.

As depraved as Crutchley was, the same could easily be said of Clawson. By his own admission, he suffered from a chromosomal abnormality that made it impossible for him to have sex with a willing partner. He had found through trial and error that forcing someone, preferably a stranger, to bend to his needs was the only thing that cured his impotence.

In the end, two juries were convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that Eugene Paul Clawson was responsible for the senseless murders of the college roommates who had simply been in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Since no death records for Clawson can be found, it is presumed that he sits in prison today — as he has for over forty years — awaiting the time when he leaves this Earth, his debt to society paid in full. While his passing can never make things right for his victims or their families, it ensures that he will never again prey upon those unfortunate enough to cross his path.

Resources:

·fayettetribune.com

·nytimes.com

·Times West Virginian

·WBOY.com

·reddit.com

·Coal Camp USA

·oxygen.com

·wvmetronews.com

Images used under provisions of the Fair Use Act for purposes of reporting and education.